The Privilege of Collapse

Our species may become extinct, but we will never again be cavemen.

“Tolerance and apathy are the last virtues of a dying society.” —Aristotle

Some ideas are off-limits to most ideological cliques. For democrats, conservatives, neoconservatives, neoliberals, well-informed social democrats, Marxists, young, hip communists, religious fanatics, business people, millionaires and billionaires, etc., overpopulation, degrowth, overshoot, the polycrisis, ecological destruction, climate change, global heating, peak oil, pollution, and “the sixth extinction” are boring, taboo subjects, only a minority of doomers concern themselves with. “Fuck doomers” sums up their attitude towards people who are concerned with existential risks.

“Idiot! Tree hugger! You have benefited from modern techno-industrial fossil-fueled liberal economics and political philosophy your whole life! Now that you’ve had fun and enjoyed consumer culture, you want to deny what you’ve had to others.” —True Believer

For the true believer, salvation comes from the progress of God. Progress is, of course, the ability to produce and enjoy more stuff.

The world is an illusion, a simulation, a place we enjoy before purgatory, heaven, or hell. If we behave well, we’ll do well enough. It’s best not to ask too many questions. Our Masters will take good care of us.

People who have worked hard to succeed in our modern techno-industrial, competitive, and expansive world will fight to maintain that world. They aren’t about to give it up. They have learned what it takes to succeed and will fight for recognition.

For true believers, the answer is always more growth. India, China, Africa, and South America should be allowed to rise to the standard of living experienced by upper-middle-class and wealthy Americans. (But not if they are too competitive. The American Empire knows best. If we are not competitive with our rivals, we kill them.) The competition for what nation or alliances control resources and economic growth is a serious business. At the very least, the world should remain exploitable so that the affluent West can maintain its standard of living and allow its wealthy elite to become even richer. The West sets the standard and knows what’s best for the world. Get with the program, and the West will take care of you. You’ll be able to shop like a millionaire. You owe all the good things in life to Corporate leaders and shareholders. Be thankful; life is short and full of bread and circuses for those who play along, for the superfans who understand the values the Players advocate.

We are motivated by the belief that if we participate in The Great Game on some level, work hard, and fight, we might become one of the few members of society that controls most of the wealth and resources in the world—thinking this gives us a reason to get out of bed in the morning. Success automatically presupposes that we know what’s best for everyone; it validates us. Buy a lottery ticket, borrow money for an Ivy League education, and fight to get to the top; you can be a winner and an elite Player at the top of The Great Game.

There is ample evidence to support the benefits of our particular ways of achieving economic growth. People have more things. Even people in less affluent countries have smartphones and more consumer goods.

“Read Steven Pinker, and shut the fuck up, Doomer Killjoy!” —True Believer

I get it. I am a white man born in the United States in the 1950s. Although I am not a wealthy Player of The Great Game, I used to provide services to Players and their enterprises and did well enough to live an interesting and exciting life. If a young person says they want to be a Wall Street Banker, I won’t tell them they are evil or crazy. I might suggest some reading. I’m not here to preach, although it can sound that way because I’m convinced that if we managed things differently, people would be much better off. But, you know, we might find ways to avail ourselves of the energy and materials to be a multi-planet consumer culture where keeping score matters most. We can all aspire to be the next Elon Musk. Best of luck, I mean, be a self-made man, a made man—whoops, mixing metaphors.

Like most people, I’m optimistic about some things and pessimistic about others. My optimism depends on the preconditions needed for a desired outcome. If not available, those conditions must be imagined, created, and implemented to initiate a cascade of events and a milieu of thought that can produce something extraordinary. When something radically new emerges, it may not be recognized at first; once it is, it may inspire adverse reactions from people used to the status quo, the customary way of doing things. Familiarity feels safe. Predictability provides us with a sense of security. In the material world, successfully navigating the day’s challenges requires knowing one’s surroundings and how things work. Practicality requires an environment where things fit and function as expected.

The core components of critical thinking, especially those related to evaluating one’s own ideas, thoughts, and feelings, are incredibly challenging to acquire and practice, especially when challenging the status quo. I will discuss this further later on in this post.

Sam is sick and doesn’t know it. His sickness doesn’t let him know he’s got a terminal disease and the world is keeping this knowledge from him. It’s an open secret best ignored.

Americans are proud and privileged people. From the moment Europeans set foot on what we now refer to as Central, North, and South America, it was a race to conquer territory and exploit vast resources. Competition and conquest define The Great Game in the Americas and Eurasia, and it’s been a brutal, rough, and, for some, extremely profitable enterprise. It still is.

America is a privileged nation.

Its Vast and Contiguous Landmass is large and unified, spanning various climates and ecosystems, facilitating internal trade, transportation, and a diverse agricultural base.

The U.S. enjoys a temperate climate suitable for agriculture that supports a dense population. Its abundant, fertile, arable land contributes to food self-sufficiency and export capacity.

Extensive, navigable waterways (e.g., the Mississippi River) have historically facilitated trade, transportation through the Midwest, and economic development. Transcontinental railroads, made possible by fossil fuels, the Industrial Revolution, and global markets, wove the United States into a vast trading network.

America’s geographic isolation from major global conflict zones has shielded the U.S. from the devastation caused by wars that many other nations have experienced. Eurasia gets hammered repeatedly while the U.S. remains protected by oceans and allies, relatively robust and wealthy trading partners with abundant energy resources.

The United States is blessed with vital natural resources and abundant coal, oil, and natural gas reserves that have fueled industrial growth and reduced its reliance on energy imports since it became a republic. Significant deposits of essential minerals like iron ore, copper, and timber underpin manufacturing and infrastructure development.

The U.S. dollar’s dominance in international trade and finance makes it the global reserve currency, granting the U.S. significant economic and political leverage. The global demand for dollar-denominated assets allows the U.S. government to borrow at lower interest rates. The dollar’s centrality in the international financial system enables the U.S. to impose impactful economic sanctions. Countries park their dollars in U.S. markets and treasuries, which help finance U.S. enterprises and defense. It has a central bank. It’s been the wealthiest country in the world for many decades.

The U.S. possesses highly developed, deep, and liquid capital/financial markets that attract global investment and facilitate capital formation. Strong institutions with robust legal frameworks and regulatory bodies foster investor confidence and economic stability. America provides the international legal code of capital that most nations are bound by in one way or another—this is known as “the rules-based order.

Gangs of New York—First Come, First Rule

The U.S. is an innovation hub that promotes a culture of entrepreneurship, which attracts talent and investment and drives technological advancement. It is a nation of immigrants, granting it a constant flow of subservient labor that can be demonized for political purposes despite almost everyone being of immigrant stock.

The concentration of financial institutions and legal expertise creates powerful network effects supporting industries in a self-reinforcing ecosystem.

Despite its flaws, the U.S. boasts a longstanding democratic system with peaceful transitions of power that contribute to stability and investor confidence. A robust legal framework protects property rights, enforces contracts, and promotes a predictable business environment. This gives the U.S. sway and influence over international institutions and alliances, allowing it to shape global norms and policies—“the rules-based order.”

The U.S. hosts many leading universities, attracting global talent and driving research and development. American culture, including music, film, and television, enjoys widespread global popularity, enhancing its soft power.

The U.S. has the world’s most powerful military, which provides security and the ability to project power globally. A network of military bases and alliances worldwide extends U.S. influence and allows for rapid response to crises. Arguably, the U.S. nuclear weapons deterrent is one primary reason we have not experienced another World War until recently, with an ongoing Fifth Generation Warfare simmering and conflicts breaking out in Europe and the Middle East. Many experts in geopolitics and the history of war believe we are already fighting World War III, a war between the Wealthy North and the BRICS.

The above accounting method, which has many advantages for America, is cursory and shallow in assessing its many strengths and privileges. Despite all of its advantages, the U.S. has always been plagued by severe challenges such as income inequality, political polarization, and social issues like racial injustice, healthcare access, and gun violence, to name but a few.

“Economic growth is not a panacea for social problems. In fact, it can often exacerbate them by creating greater inequality and social division.” —Joseph Stiglitz

The U.S. enjoys many privileges contributing to its global standing, but these advantages don’t automatically translate into a problem-free society. I would argue that its “success” has created an ideological and material machine, what Nate Hagens calls The Superorganism, that is omnicidal and threatens the survival of homo sapiens. America is the epitome of a modern, technological, industrial society, a resource and energy-driven beast that grows for the sake of growth like a cancer upon the Earth.

If the United States can’t reform itself, the world is doomed. Much has been written on these subjects, and many organizations and individuals are trying to envision what this transformation might look like.

Our way of life, worldview, and thought processes are habits—we take them for granted. Our culture makes sense; our way of doing things has a history and is justified through stories, social structures, institutions, law, religion, and custom. We absorb all of this naturally through our relationships, interactions, and education through the practice of living our lives.

“Tradition is a guide and not a jailer” —W. Somerset Maughamailer

Constraints and limitations allow us to discover and invent new ways of thinking and doing things; they challenge and inspire us to solve puzzles and achieve breakthroughs, transform hopes and dreams into mundane reality, and liberate new potential.

Is it possible to describe limits to imagination? Some are more imaginative than others, but collectively, through the networked interplay of ideas, our imagination may be limitless. And yet, the nature of our consciousness is contained within the limits of our species, and whatever we discover or invent must be but a fraction of what is possible in the grand order of the Universe. Our inherent capacity to think and feel limits whatever powers we imagine God has and our ideas about what the Universe is and how it arose. It is reasonable to believe that our understanding of ourselves, the nature of life on Earth, and our place in the Universe is explainable through science or stories or merely an ephemeral expression of the configuration of constantly evolving and emerging properties of the interplay of energy and matter. Choose a metaphor or turn of phrase. Consolidate your evidence and expound a theory, try to falsify it, and achieve a consensus. Make sense of it all somehow, and rest assured. But still, we don’t know the half of it. We live in a world of limits that will surely end and be transformed into something else.

“To develop a complete mind, study the science of art, study the art of science. Learn how to see. Realize that everything connects to everything else.” —Leonardo da Vinci

I am not a physicist, theoretical mathematician, or mystic. When I contemplate “the void,” time, or infinity, I feel like I’m floating in images and ideas I can’t grasp, buffeted by fleeting feelings of euphoria and terror. I cannot construct models, understand what they would be based on, or comprehend their inherent fragility. Grand ideas are rather vague for me. I feel small and insignificant when I overthink things I can not know, but I am compelled to search for answers anyway.

When an expert physicist describes the work in layperson’s terms, I understand the subject, but my knowledge is still uncomfortably shallow because I still can’t do the math. I could acquire the skills needed if I spent time and energy immersing myself in the culture of science, physics, and maths and perhaps have some confidence in experiencing an original thought. One can say something similar about any domain of expertise that requires time and hard work to comprehend and use. Passionate interests requiring sacrifice and hard work are rewarding in and of themselves—no achievement is necessary.

“The reward for work well done is the opportunity to do more.” —Jonas Salk

Wouldn’t it be fantastic to have one hundred active years to explore various domains of interest and to live in a culture focused on learning? Why focus on education and lifelong learning? It’s crucial to our continued survival and flourishing, and valuing the understanding of Great Nature above all leads to a healthier life for all, including plants and animals. I want to live in a world of loving people devoted to life where everything is sacred.

“A nation's culture resides in the hearts and in the soul of its people.” —Mahatma Gandhi

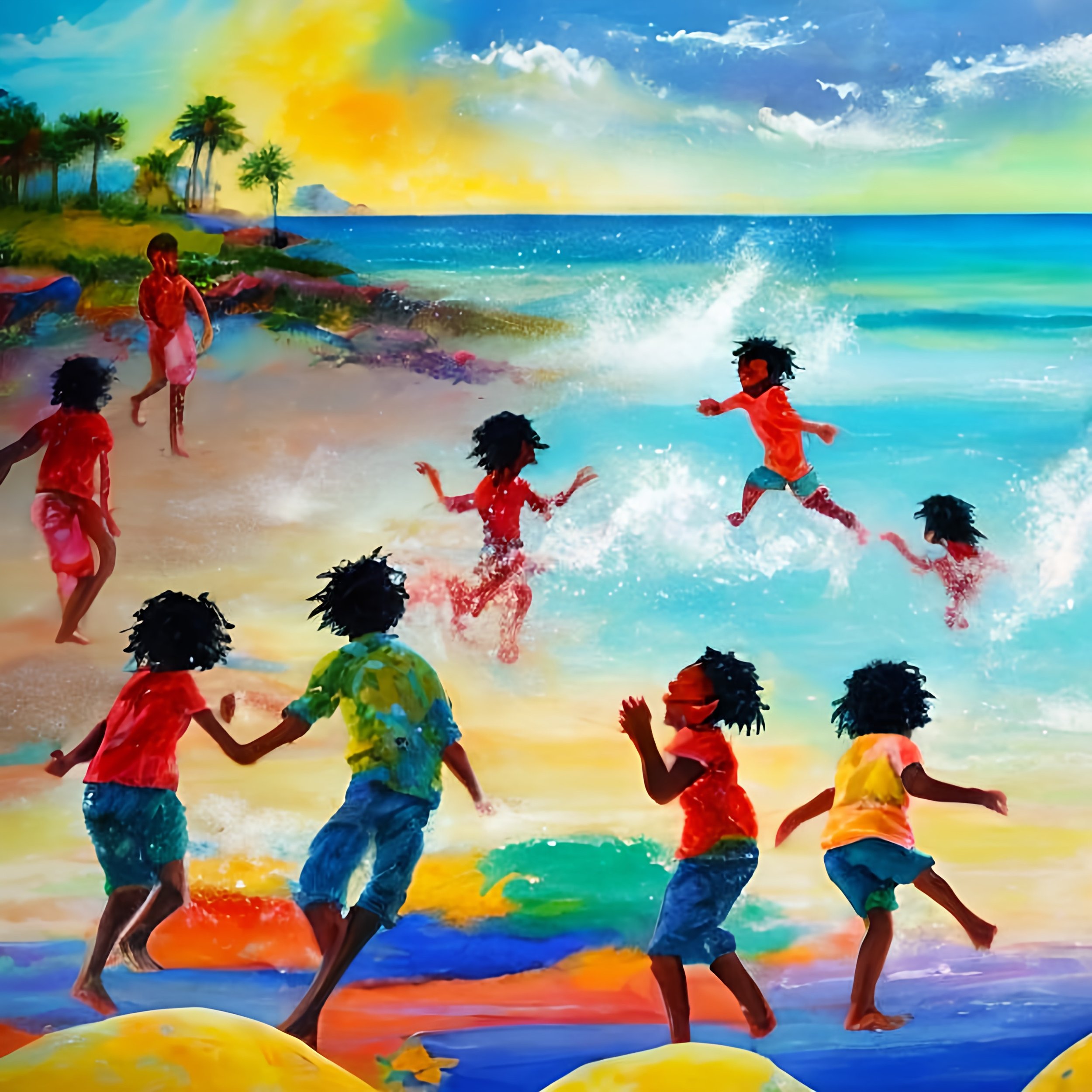

Imagine a world with a population of a billion people where your basic needs were easily provided for, and your culture was devoted to learning about nature and personal growth.

In our new culture, children are treasured; everything is done to make them feel secure and well-loved and to develop their talents.

Children grow up so fast. In our new world, we cherish spending quality time with our children and revere our relationships with them. Caring for children in our community is a joy, a paramount privilege, and a sacred duty.

Imagine we had a “resource-balanced” economy, and our way of life used far fewer resources than it does now. Could we maintain some form of modern industry like Simon Michaux suggests, with sensible, enlightened environmental and material stewardship without ultimately destroying our habitat?

"The economy is a wholly-owned subsidiary of the environment, not the other way around." —Gaylord Nelson

Limits of the Circular Economy

The Circular Economy (CE) is a proposed model for a sustainable industrial ecosystem. It aims to address the flaws of the current Linear Economy, which relies on the continuous consumption of natural resources and the disposal of waste products. However, the CE in its current form is structurally flawed and faces several limitations.

This is one of many such proposals we’d do well to contemplate.

These limitations include:

Energy Requirements: The CE fails to fully account for industrialization’s energy requirements. While it advocates for renewable energy sources, it does not adequately consider the energy needed to construct and maintain a renewable energy infrastructure, which relies heavily on fossil fuels.

Energy Returned on Energy Invested (ERoEI): The ERoEI for renewable energy systems is generally lower than that of fossil fuels, implying that more energy is needed to produce the same amount of usable energy. The CE does not factor in this crucial aspect of energy efficiency, which will affect the overall feasibility of the transition.

Non-Recyclable Materials: Many materials, such as clay minerals and certain specialty metals, cannot be recycled effectively and are often lost to the environment. The CE does not provide a comprehensive plan for managing these finite resources.

Limits of Recycling: While some metals can be recycled repeatedly, the quality of recycled materials degrades with each cycle, eventually becoming unusable. The CE does not account for these practical limitations of recycling.

Role of Mining: The CE downplays the role of mining in supplying the raw materials needed for the transition to renewable energy and other sustainable technologies. The large-scale deployment of renewable energy systems will necessitate an unprecedented increase in mineral extraction, which the CE does not address.

International Competition: The CE focuses on securing resources for Europe while operating within a globalized raw materials market dominated by China. This approach ignores the geopolitical realities of resource control and international competition, which could undermine the CE’s goals.

Population Growth: The CE’s closed-loop model, based on recycling waste streams, does not allow for human population growth, which requires a continuous influx of new resources.

Economic Growth: The CE is incompatible with the current economic paradigm of continuous growth, which inherently requires the consumption of ever-increasing amounts of resources.

Zero Waste: While desirable, zero waste is impractical in any industrial society. Zero waste is untenable and an impossibility in our material world. The CE’s emphasis on zero waste could lead to unrealistic expectations and hinder the development of pragmatic solutions.

Logistics of Material Transport: The CE does not adequately consider the logistical challenges of transporting materials between disposal and reuse points, especially as the global energy landscape shifts.

These limitations suggest that the CE, while a good starting point, is not a viable solution in its current form. To achieve sustainability, a more realistic and comprehensive approach is needed. A Resource-Balanced Economy (RBE) is a potential evolution of the CE. There are other models for sustainable technological and industrial societies, and all should be considered. Circumstances may dictate that future generations live hunter-gatherer lifestyles, but for now, we must explore every possible outcome we can. This is not to say that an RBE economy or something like it would be the best of all possible worlds, but a future where humans can explore the limits of the possible seems inherent to our species. We can’t help but learn and explore. Maybe our curiosity will be the death of our species, but we don’t know that yet; there may still be hope that our continued exploration of the Universe is tenable.

“We are facing a global crisis of unsustainable consumption and production patterns that are destroying the environment and exacerbating social inequalities.” —UN Secretary-General António Guterres

Imagine that people didn’t care much about fleeting fashions, status, or competition for power and control. We still enjoyed dynamic recreational activities, competitions, games, and pastimes but earned most of our accolades through our love of learning and ability to live harmoniously together.

In this culture, we mostly play for the first twenty-eight of our lives. We are free to explore under the supervision of loving adults in our community. Every adult is a teacher. We experience childhood in safety and security. Through various activities, we acquire vital skills: discipline, focus, concentration, attention, physical fitness, music, dance, reading, writing, and arithmetic. We also internalize our culture’s core values. We do these things playfully. Play in our culture is serious work.

During this period, we are ostensibly exposed to all critical domains of interest and encouraged to attend to various subjects as much or as little as we like. We also do our chores and help adults with essential work part-time.

Our culture has all the resources needed for lifelong learning. Every child can pursue their interests. Our communities are small enough to be intimate and large enough to exert a powerful network effect. All communities are networked regionally and worldwide, engaging in annual festivals and events. Energy and materials are managed carefully for maximum economy. All populations live within sustainable, natural limits. Consumerism is a relic of the past. We manufacture what we need to live well and grow spiritually, intellectually, and creatively. How this is achieved is not discussed here; let’s give ourselves the freedom to imagine a radically different world inhabited by a new kind of homo sapiens, one worthy of its name.

Our Early Encounter With “The Humanities”

While we play, we learn about the human condition, history, and how to listen and express ourselves.

We are exposed to deep time, ancient history, medieval history, modern history, world history, social history, cultural history, art history, and economic history. We learn from factual data and multiple lines of evidence and are free to view the past from many different perspectives: critically, objectively, and creatively.

We study written and spoken language, including literature, linguistics, and rhetoric. The world has regional languages and one common language everyone understands and speaks. We are exposed to world literature, including classic and contemporary literature. We study literature across time, cultures, and languages. We learn the craft of writing fiction, poetry, and drama. We learn practical writing for nonfiction subjects. We study the science of language, its structure, and meaning. We preserve and rediscover languages of the past.

At the center of every large town is a university with a library in the center of the campus. The library is always the largest and most beautiful municipal building, with many facilities within its walls. It allows for easy access to the world’s knowledge, information packets, and information delivery and storage systems that have been lovely and painstakingly developed over generations, providing the foundation and structure of culture.

Biological and cultural evolution can favor traits that benefit individuals, groups, and healthy, vibrant ecosystems. Intellectual curiosity drives individuals to explore and learn, leading to better problem-solving and adaptation. Cooperative individuals are more likely to survive and thrive in group settings, as collaboration allows for better resource management and maintenance. Empathy fosters strong social bonds and reduces conflict, promoting cohesion and stability. Stewardship, or responsible use of resources, ensures long-term sustainability and benefits future generations. Over time, these traits can become more prevalent within a population through natural selection (in the case of biological evolution) or cultural transmission and learning (in the case of cultural evolution).

What do communities look like in our new world?

Let’s avail ourselves of the work done by Robin Ian MacDonald Dunbar, a British biological anthropologist, evolutionary psychologist, and specialist in primate behavior. Robin Dunbar is professor emeritus of evolutionary psychology of the Social and Evolutionary Neuroscience Research Group in the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford. He is best known for formulating Dunbar’s number, a measurement of the “cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom anyone can maintain stable relationships.” Later, we’ll focus more on limits to growth and ideal population levels of humans when living according to the ethics of our culture and how our population would be maintained.

Dunbar’s Number and its Layers:

Core: 5 closest relationships (loved ones)

Close Friends: 15

Friends: 50

Meaningful Contacts: 150

Dunbar’s number suggests that 150 is the cognitive limit for maintaining stable social relationships. However, in my somewhat utopian scenario, this doesn’t necessarily equate to an optimal community size for sustainability, harmony, and creativity.

Beyond Dunbar: Optimal Community Size

100-150: Sustainability advocate Ben O’Callaghan, based on intentional community experiences, suggests this range. Larger communities risk anonymity and decreased social cohesion, while smaller ones might lack diversity and resilience.

45-65 adults: Some research indicates this range fosters effective collaboration and decision-making within a community or enterprise.

25-30 families: Historically, successful communities like the Anabaptists thrived with this size, allowing for close bonds and shared responsibilities.

Factors Influencing Optimal Size:

Purpose and Values: A community focused on shared work or specific goals might function well with a smaller size, while a more diverse community might benefit from a larger population.

Resource Availability: Access to land, water, and other resources can influence the number of people a community can sustainably support.

Technology and Infrastructure: Modern communication and transportation can facilitate connections in larger communities, potentially increasing the optimal size.

Social Organization: Effective governance structures and decision-making processes become increasingly crucial as community size grows.

Considerations for Sustainable Communities:

Social Cohesion: Maintaining strong social bonds, trust, and a sense of belonging is crucial for community well-being and resilience. This does not necessarily require a “new religion.” People are storytellers and dreamers. Social cohesion in our new world will involve more than myths and beliefs and be intertwined with our understanding of Great Nature.

Economic Viability: The community should have a diverse and resilient economic base to meet its members’ needs. This requires us to devote a library of books discussing the meaning of economy and economics. In our new world, economics has nothing to do with financial markets, just time manufacturing or shopping malls. If we are not to become cave-dwelling hunter-gatherers in the future, should we survive our weapons of mass destruction, anthropogenic global heating, and the many other existential challenges of the polycrisis, we must reconcile the domain of economics. What we have taken for granted must be left behind and radically transformed. There is little the current school of economics has to offer that will benefit us in the future.

Environmental Sustainability: Practices should minimize environmental impact and ensure the long-term health of the ecosystem.

Governance and Decision-Making: Inclusive and effective governance systems are essential for managing resources and resolving conflicts. Great Nature will lead the dance, and something akin to true democracy will emerge.

If we (a critical mass of people) could envision and implement a radical path to a new way of living together, we’d have the opportunity to ultimately discover the “optimum” size for intimate and sustainable communities, balancing social connection, resource management, and effective organization to create thriving, enduring communities. A deep future presupposes continued cultural and species-wide evolution. Great Nature has its way, and it’s our responsibility to be guided by it.

We currently know no strict limit to the optimal size of a larger town or small city. Experts suggest towns ranging from 2,000 to 10,000 could effectively utilize our imagined model. The key lies in maintaining strong links between Dunbar nodes, facilitating communication, collaboration, and a sense of shared identity and purpose across the larger communities and networks of communities worldwide.

Groups that do not conform to strict growth limits and moral and ethical practices would be broken up and absorbed by other communities or destroyed, just as our body’s immune system destroys a pathogen.

The Venus Project and many other organizations have envisioned how communities might be designed and constructed using local, renewable resources and materials that can be easily maintained without layers of extreme complexity. We can redesign and reengineer over coming generations, considering our current predicament's imposed limitations, or give up and accelerate towards collapse. Young people need something beautiful to work towards.

Examples of such communities include ecovillages, co-housing emphasizing common spaces and shared resources, and neighborhood-based planning prioritizing walking, bicycling, and mixed-use developments with shared workshops, gardens, and recreation spaces.

Effective democratic-style governance, shared resources, including coops, enabling a resilient local “economy” that reduces the reliance on external resources, and technological integration are vital to strengthening cohesive connections between Dunbar nodes across larger community structures.

Much has been written about why alternative communities fail. Inexperienced founders, lack of resources (usually financial), and complicated interpersonal relationships can contribute to such failures. Still, by far, the thing holding back alternative communities is the permeant, ubiquitous economic religion that global civilization is based on and adheres to. This is a considerably comprehensive subject worth looking into in depth. Currency, trade, ownership, property rights, the commons, investment, value, and markets must be reimagined and redeveloped into a system of stocks and flows that are not so riddled with adverse externalities and stress.

“Nature does nothing uselessly.” —Aristotle

In our new world culture, a holistic approach, taking into account systems and complexity theory, is central to its development over generations to keep our community’s ecological footprint at the forefront of our concerns, one that minimizes resource consumption, waste production, and environmental impact. Humans should identify with and blend into Great Nature, trying not to interfere with its evolutionary continuance; social equity ensures access to the things one needs to live a high-quality, healthy, secure life with ample opportunities for personal growth. And we must always strive to economize.

"The endless pursuit of economic growth is not only unsustainable but also deeply unsatisfying. It leads to a society that is always striving for more, but never truly content." —Dalai Lama

Let’s get back to our early education.

“The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” —Socrates

First and foremost, young people are exposed to critical thinking skills throughout their education.

Core Skills for Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the ability to analyze information objectively and make reasoned judgments. It involves questioning assumptions, considering different perspectives, and forming well-supported conclusions.

During one’s teenage years, we gradually delve more deeply into the following practices:

Analysis: Breaking down information into its components, identifying patterns and relationships.

Interpretation: Understanding the meaning and significance of information, including its context.

Inference: Drawing conclusions based on evidence and reasoning.

Evaluation: Assessing the credibility of sources, the strength of evidence, and the validity of arguments.

Explanation: Clearly and effectively communicating one’s reasoning and conclusions.

Self-Regulation: Reflecting on your thinking process, identifying biases, and correcting errors.

Bayesian Probability and Reasoning

Bayesian reasoning is a powerful tool for critical thinking. It's a method of updating your beliefs based on new evidence. Here's the basic idea:

Prior Probability: You start with an initial belief about something (your prior probability).

New Evidence: You encounter new information or data.

Updating Beliefs: You use Bayes' theorem (a mathematical formula) to update your belief based on the strength and relevance of the new evidence. This results in your posterior probability.

Example:

Imagine you think there's a 30% chance it will rain tomorrow (your prior probability). Then you see a weather forecast predicting a 70% chance of rain. You use this new evidence to update your belief, and now you think there's a higher probability of rain. Bayesian reasoning provides a framework for incorporating new information and refining your judgments.

Cognitive biases and heuristics are explored and understood, as well as common logical fallacies.

Motivated Reasoning, Groupthink, and Other Biases

Motivated Reasoning: This is the tendency to interpret information in a way that confirms pre-existing beliefs. We're more likely to accept evidence supporting our thoughts and dismiss evidence challenging them, which can be a major obstacle to critical thinking.

Groupthink occurs when a group's desire for harmony or conformity results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus without critically evaluating alternative viewpoints.

Confirmation Bias: A tendency to search for or interpret information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions.

Availability Heuristic: Overestimating the importance of available or easily recalled information, often leading to biased judgments.

Bandwagon Effect: The tendency to do (or believe) things because many others do (or believe) the same.

Here are some more biases and heuristics that profoundly influence our ability to see things as they are and imagine how things might be different.

Authority Bias: The tendency to attribute greater accuracy to the opinion of an authority figure (unrelated to its content) and be more influenced by that opinion.

Example: Blindly following the advice of a doctor even when it contradicts your research or the scientific and evidence-based consensus.

Availability Cascade: A self-reinforcing process in which a collective belief gains more and more plausibility through its increasing repetition in public discourse (or "repeat something long enough and it will become true").

Example: A minor news story about a shark attack gets repeated and amplified, leading to widespread fear of sharks even though statistically, such attacks are sporadic and rare.

Declinism: The predisposition to view the past favorably and the future negatively.

Example: "Things were so much better in the old days" — often without concrete evidence to support this claim.

Framing Effect: Drawing different conclusions from the same information, depending on how that information is presented.

Example: People are more likely to buy meat labeled "80% lean" than meat labeled "20% fat," even though they are the same.

False Consensus: The tendency to overestimate the extent to which others share our beliefs and behaviors.

Example: Believing that most people agree with your political views, even though this might not be true.

Halo Effect: The tendency of an impression created in one area to influence opinion in another.

Example: Assuming that a physically attractive person is also intelligent and kind.

Dunning-Kruger Effect: A cognitive bias whereby people with low ability at a task overestimate their ability.

Example: Someone who is a poor public speaker but believes they are very good at it.

Appeal to Emotions: Manipulating an emotional response in place of a valid or compelling argument.

Example: Using fear or anger to persuade people instead of presenting logical reasons.

Filter Bubbles: Intellectual isolation that can result from personalized searches when a website algorithm selectively guesses what information a user would like to see based on information about the user, such as location, past click behavior, and search history.

Example: Social media feeds only show you news and opinions that align with your views.

Ingroup Bias: The tendency to favor members of one's group over outgroup members.

Example: Showing preferential treatment to people who are fans of the same sports team as you.

Gambler's Fallacy: The belief that past events influence future random events.

Example: Believing that the next flip is more likely to be tails after a series of coin flips landing on heads.

Post-Purchase Rationalization: Persuading oneself through rational argument that a purchase was good value.

Example: Convincing yourself that an expensive gadget was worth the money after buying it.

Observational Selection Bias: Noticing something more often after you begin to pay attention to it, leading to the belief that it has increased in frequency.

Example: Seeing more red cars on the road after buying a red car yourself.

Negativity Bias: The tendency to pay more attention to negative experiences than positive ones.

Example: Dwelling on a single criticism in a performance review, even if it was overwhelmingly positive.

Projection Bias: Assuming that others share the same feelings, values, and beliefs as you do.

Example: Believing that your friend will love the same movie that you did.

Anchoring Effect: The tendency to rely too heavily on the first piece of information offered (the "anchor") when making decisions.

Example: Being influenced by the initial price of an item, even if it's later discounted.

Current Moment Bias: Preferring a smaller immediate reward to a larger later reward.

Example: Watching TV now instead of studying for an exam a week away. Humans have a tough time imagining ourselves in the future and altering our behaviors and expectations accordingly. Most of us would rather experience pleasure in the current moment while leaving the pain for later. This bias is of particular concern to economists (i.e., our unwillingness not to overspend and save money) and health practitioners. Indeed, a 1998 study showed that, when making food choices for the coming week, 74% of participants chose fruit. However, when the food choice was for the current day, 70% chose chocolate.

It’s impossible to consistently and continually police one’s thoughts to avoid these cognitive traps. Still, the sooner one is aware of how cognitive biases can impair one’s judgment, the sooner one can slow down and think more carefully when making important decisions or choosing critical courses of action. Read Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman.

In our new world, we raise children who can think as clearly as possible.

Why People Conform

Humans are social creatures, and belonging to a group is essential to our well-being. Here's why we try so hard to fit in:

Survival and Security: Historically, being part of a group increased our chances of survival and protection.

Social Acceptance: We crave acceptance and belonging. Being excluded can be emotionally painful.

Validation: Groups reinforce our beliefs and values, making us feel confident in our worldview.

Status and Resources: Group membership can provide access to resources, opportunities, and social status.

The Challenge of Changing Culture

People invest a lot in their careers, and challenging the status quo is risky. We may fear losing our position, social standing, or sense of identity within that culture.

The Role of Education

Traditional education often emphasizes memorization and compliance rather than critical thinking and questioning. This can perpetuate the status quo by producing individuals who are well-equipped to function within existing systems but less prepared to challenge or change them.

Lippmann and Public Opinion

Walter Lippmann's "Public Opinion" is a classic work exploring how stereotypes, biases, and limited information shape our world perceptions. He argued that people often rely on simplified mental models, or "stereotypes," to make sense of the world, and these stereotypes can lead to flawed judgments and decisions.

Overcoming these Challenges

Developing strong critical thinking skills is essential for navigating these complexities. Here are some strategies:

Be Aware of Your Biases: Recognize that everyone has biases. Reflect on your thinking, and actively seek out diverse perspectives.

Question Assumptions: Don't take things for granted. Ask "why?" and challenge the underlying assumptions behind beliefs and practices.

Seek Evidence: Base your judgments on solid evidence rather than opinions or emotions. Be open to changing your mind when presented with new information.

Consider Alternatives: Explore different viewpoints and consider alternative explanations. Don't be afraid to challenge the status quo.

Encourage Open Dialogue: Create spaces where people can safely express different opinions and engage in constructive debate.

By cultivating critical thinking skills and actively challenging biases, we can make more informed decisions, foster more inclusive cultures, and create positive change.

"The modern world's obsession with economic growth is a form of collective insanity. We are sacrificing our planet, our communities, and our very souls on the altar of GDP." —Vandana Shiva

In our new culture, we comprehensively explore world philosophy, which consists of fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. We delve into metaphysics, which investigates the nature of reality from a subjective perspective. We study epistemology, ethics, logic, political philosophy, and aesthetics.

There is an academy of religion, theology, comparative religion, history of religion, philosophy of religion, contemplative arts (prayer and meditation), paganism, animism, and other spiritual and contemplative ways of living. The best way to avoid the pitfalls of the True Believer is to examine beliefs

We have performing arts facilities for learning, practicing, and presenting music, dance, and drama.

Visual arts academies exist throughout all communities, where people study the craft of various visual arts. These academies have facilities for displaying drawings, paintings, sculptures, photography, motion pictures, computer graphics, animation, special effects design, multimedia, and other arts.

Municipal facilities are shared among several larger communities of Dunbar nodes connected by sustainable transportation systems, including cycling and walking paths. Automobiles are shared, roads and highways are significantly reduced, and only emergency and utilitarian vehicles are permitted in larger communities.

Our culture’s approach to the humanities is integral. The humanities draw on each other to provide a more complete understanding of human experiences. They are constantly evolving, with new areas and inquiry approaches continually emerging.

People gravitate towards sports, games, and activities they like. In addition to the many sports available to engage in and practice, young people are exposed to the interconnected disciplines in sports-related fields.

Sports science, sports medicine, sports psychology, sports coaching, and management are taught, researched, and developed to enhance one’s sporting activities in a pro-social, safe, and healthy way.

We train, study, play, and perform various things or bounce around exploring different activities and groups of people. We have romances, triumphs, failures, and heartbreaks. We rise and fall and learn how to build relationships. We are resilient people who know how to bounce back.

Some are better than others at mastering the skills necessary to understand and excel in a given domain, but all have access and time to establish a high degree of knowledge in each area. Those with more ability would mentor and tutor those with less and develop profound relationships of trust and interdependence. Masters of arts and domains are sought after and given respect and responsibility.

We are not hunter-gatherers or cave dwellers anymore; the genies have been out of the bottle for ages—what makes us different is our ability to tame them and make them humane in the best sense.

Education is the process of developing and enhancing the better angels of our nature.

One Hundred Years of Inquiry Is Primarily Devoted To The Natural Sciences

We can discuss how practical work is done later; we’re interested in experience, inquiry, and education. In our new world culture, it’s not hard to get things done; although some things are more complex and involved, the regular business of life is simple and relatively pleasant, and “dirty jobs” are part of getting on with it. I am giving myself the freedom to imagine what might produce a different focus that could jolt us out of our profit-based, sinful, conquering dualistic delusions that have brought our global civilization to the brink of collapse and possibly extinction. I may be embarrassed by my imaginings in some months or years, but that’s ok; I don’t mind being foolish when I imagine different worlds.

In my world, understanding the nature of things as far as we can in any generation, how nature works, and how we can thrive long-term in harmony with our ecosystems, habitats, and environments is paramount. It is unwise not to know how profoundly connected we are to everything else, to every sacred thing and system, great and small, no matter how complex or incomprehensible.

In our new culture world, people live much longer. Nice, right? Pick a number. 130 years? 150? Or maybe it’s just that the continuity of life from generation to generation is treasured; we feel connected to posterity. Our endeavors are seen as things our communities will never finish or achieve, so we pass on long-term projects to posterity, knowing the work will continue. Why do we need to live longer? I can’t explain the details, but the main reason is that I am a slow learner. Even if everything in our life were optimized for maximum flourishing and personal growth, we’d still have too many things on our bucket list when we passed. All good people need more time to create what’s passed on to future generations. More people in our culture will be able to become wise apes and know what to do with their wisdom.

We still have diseases and accidents, but there are no wars, and the health of people and ecosystems is of paramount concern. We keep learning how to extend human life and remain mindful of what that means to living systems. We become caretakers, not exploiters of life. Things are not commodified; they are cherished.

Remember, all animate and inanimate things are sacred. We deeply love our world and are devoted to living things. We understand the balance of nature and how creatures live and die. Our lives are long, so we carefully plan our population’s growth and care for children personally and collectively. We practice an ethic of quality over quantity. Our possessions are few, and we all feel ownership for our regard and responsibility as stewards of our communities and environment. We have a powerful sense of belonging. Forests, lakes, oceans, mountain ranges, deserts, grasslands, and all interconnected living systems are cherished and cared for like family members. We treat living systems and places with reverence and respect. Our connection with life, things, and places is blissful, sustaining, and energizing.

We all share our living spaces with friends and family and consider the world our home. We have healthy, fresh food and clean water to drink. We have renewable energy systems that can power machines without which we can’t live and learn. Again, we manage our material and energy resources carefully and with posterity in mind.

We hold regular festivals with the seasons and enjoy dancing, making music, singing together, and telling stories. We aren’t best friends with everyone but are friendly, respectful, and thankful for what each individual brings to the group.

The following is a partial outline of our focus of inquiry during the first half of our long lives. The amount of time we spend on each element depends on several factors: our interests, time allocation, practical constraints, aptitudes, and eventually, our decision to become experts in various domains of activity, inquiry, development, industry, and invention. We are all autodidacts supported by communities of teachers with ample resources to share their knowledge.

A primary focus is on the physical sciences. (We can’t help ourselves; we have become genie tamers.)

The study of non-living matter and energy.

Physics: the study of matter, motion, energy, and their interactions.

Classical Mechanics

Electromagnetism

Thermodynamics

Quantum Mechanics

Optics

Acoustics

Astrophysics

Nuclear Physics

Particle Physics

Condensed Matter Physics

Chemistry: The study of the composition, structure, properties, and reactions of matter.

Organic Chemistry: Carbon-containing compounds.

Inorganic Chemistry: Compounds not primarily based on carbon.

Physical Chemistry: The study of physical principles in chemical systems.

Analytical Chemistry: Identifying and quantifying components of substances.

Biochemistry: Chemical processes within living organisms.

Nuclear Chemistry: The study of radioactive substances.

Earth Science: The study of the Earth and its systems.

Geology

Oceanography

Meteorology

Paleontology

Environmental Science: The study of the environment and its interactions.

Geophysics

Hydrology

Glaciology

Astronomy: The study of celestial objects and phenomena.

Planetary Science

Cosmology: The study of the origin and evolution of the universe.

Astrobiology (also xenology or exobiology): The study of life in the universe.

2. Life Sciences (Biology): The sciences focus on living organisms.

Ecology: The study of the interactions between organisms and their environment.

Zoology

Botany

Microbiology: The study of microorganisms.

Genetics: The study of heredity.

Evolutionary Biology: The study of the changes in organisms over time.

Cell Biology: The study of cells.

Molecular Biology: The study of biological molecules.

Physiology: The study of the functions of organisms.

Anatomy

Developmental Biology: The study of how organisms grow and develop.

Immunology

Marine Biology

Biophysics

Biochemistry

Geochemistry

Astrobiology

Nanotechnology

Synthetic Biology

Climate Science

Our new culture prioritizes maintaining healthy and peaceful communities while maintaining biodiversity and healthy, evolving ecosystems. It will take generations—time we don’t have if we are aware of our polycrisis and the stubbornness of belief systems that dictate our behavior—and we can’t do anything well without understanding how nature works.

A Bit About Cultural Anthropology

I can’t cover everything here as I want to get to the point that the title of this article alludes to. I will leave psychology out for now and limit the rest of this piece to a discussion of cultural anthropology and the possibility that our species could create a cultural superstructure within which various unique cultures could thrive and express themselves without shattering all the complex systems our lives and communities depend on.

Again, much has been written. Hopefully, these kinds of resources and references will provide context to guide your inquiry into culture building and radical social change.

How we prosecute such a radical transformation will be left for another time to explore. I am a simple fool imagining a different world. I am exploring a tiny part of the picture without much detail, one of many possible jumping-off points.

Anthropology is the study of humanity, and within that vast field, cultural anthropology takes center stage in exploring the incredible diversity of human societies and the intricate ways we create meaning in our lives.

Culture is learned and shared, not innate. Culture is not something we’re born with; it’s learned throughout our interactions with others and the world around us.

Culture is a system of shared beliefs, values, practices, symbols, and behaviors that give meaning to our lives and allow us to navigate our social world. We are highly social animals. None of us could survive for long or live a high-quality life without the help, cooperation, and collaboration between ourselves and others.

Patterns and norms evolve and take root in our communities, shaping how we think, feel, and act.

Ethnographic fieldwork, in which cultural anthropologists spend extended periods living within a community, participating in daily life, and observing social interactions, helps us understand different expressions of culture.

My parents had a travel agency in the 60s. Before I was ten years old, I had traveled to Africa, Japan, Europe, and Mexico. Between the ages of ten and twenty, I traveled around the world again and repeated this feat every decade until I turned fifty. I spent my childhood and teen years in Ireland and Colorado. I have lived and worked in seven countries. At a stretch, I might be able to claim amateur cultural anthropologist status. I made up a story when I lived in Hong Kong while hiking with friends in an area of Hong Kong Island known as The Peak, where the international uber-wealthy occupy many homes. I talked about a group of anthropologists quietly observing wealthy families doing their daily activities at these homes. I called this story Guailo In The Mist, a riff on Gorillas In The Mist, a movie about the adventures of Dianne Fossey. My musings implied that the uber-wealthy were practically a different species.

But I digress. Let’s explore the field of anthropology some more.

Ethnographic fieldwork is a hallmark of cultural anthropology, where anthropologists spend extended periods living within a community, participating in daily life, and observing social interactions. Immersion is a key aspect of this work, providing anthropologists with an opportunity to participate in and observe the culture and gain firsthand insights from the perspective of its members while building relationships, rapport, and trust.

Key Concepts in Cultural Anthropology:

Cultural Relativism is a core code that emphasizes the importance of understanding cultures on their terms rather than judging them based on the standards of one's own culture.

Ethnocentrism is the tendency to view one's culture as superior and judge other cultures based on its norms.9 Cultural anthropologists strive to avoid ethnocentrism in their research.

Holism: A holistic approach involves considering all aspects of a culture—economy, politics, religion, social organization, art, etc.—to understand how they are interconnected.

Symbolism: Analyzing how cultures use symbols (objects, words, actions) to create and communicate meaning.

Areas of Focus within Cultural Anthropology:

Kinship and Family: How different cultures define family structures, roles, and relationships.

Economic Anthropology: How cultures produce, distribute, and consume goods and services.

Political Anthropology: How power and authority are organized and exercised within different societies.

Religion and Ritual: The role of religion and ritual in shaping cultural beliefs and practices.

Art and Aesthetics: How different cultures express themselves through art, music, and other creative forms.

Medical Anthropology: How cultures understand and address health and illness.

Environmental Anthropology: The relationship between cultures and their environment.

The Importance of Cultural Anthropology:

Understanding Human Diversity: Provides insights into the incredible range of human experiences and cultural expressions.

Challenging Ethnocentrism: Helps us recognize and appreciate cultural differences.

Promoting Cross-Cultural Understanding: Essential for navigating an increasingly interconnected world.

Addressing Social Issues: Can contribute to addressing issues like inequality, poverty, and conflict by providing a deeper understanding of their cultural contexts.

In essence, cultural anthropology provides a rich and nuanced perspective on the human story, helping us appreciate the diversity of ways that people live and make meaning in the world. The way things are now in a given culture is not etched in stone; they are fluid, malleable, and subject to creative influences and choices based on well-considered and digested elements of our human experience.

So what about privilege?

The relentless pursuit of entertainment and material wealth has created a myopic bubble around many in the wealthy West, blinding them to the true scale of the polycrisis engulfing our world. Bombarded with too much indigestible information, fleeting distractions, and consumerist desires, they struggle to grasp the interconnected nature of climate change, ecological collapse, social unrest, inequality, and economic instability. The immediate gratification of a new gadget, social media, pundits and gurus on “The Tubes,” the news, abundant entertainment, global supply chains putting food on the shelves and parts in our smartphones and cars, or a weekend getaway overshadows the long-term consequences of unsustainable lifestyles. This preoccupation with material comfort and fleeting pleasures fosters a dangerous disconnect from the natural world and the urgent need for systemic and structural change. It's a tragic irony that a society so focused on individual advancement may need to face a collective breakdown before recognizing the necessity of living in balance with nature and each other. Perhaps only when the foundations of their consumerist paradise crumble will they awaken to the fragility of their existence and the actual cost of their detachment from life’s well-being.

We won’t contemplate the possibility that our way of life is self-terminating. Do we even care if it is? Every living thing eventually dies.

Supernova. Earth will probably not even exist when the sun dies. The sun is slowly expanding. In about 5 billion years, the sun will enter the red giant phase. During this phase, the sun makes a transition from burning hydrogen in the core to burning hydrogen around the core, which has been converted into helium by hydrogen burning.

Life begets life.

The principle that "life begets life" is a cornerstone of biology. It refers to the observation that all living organisms originate from other organisms through reproduction. Countless scientific observations and experiments have supported this principle, and it is one of the key features that distinguishes living things from non-living matter. While abiogenesis, the origin of life from non-living matter, is still an area of active research, it is generally accepted that all life on Earth today originated from a single common ancestor billions of years ago.

Life and Entropy

Life appears to defy the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy (disorder) of a closed system always increases over time. Living organisms are highly ordered systems, and they maintain their complexity by constantly taking in energy and expelling waste products. This process, known as metabolism, allows living things to decrease their entropy temporarily, but it does so at the expense of increasing the entropy of their surroundings. In other words, life is a localized decrease in entropy, made possible by a greater increase in entropy elsewhere.

Life and Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics, the study of energy and its transformations, provides a fundamental framework for understanding life. The first law of thermodynamics, also known as the law of conservation of energy, states that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed from one form to another. Living organisms constantly convert energy from one form to another to power their metabolism, growth, and reproduction. As mentioned earlier, the second law of thermodynamics explains why living things must constantly take in energy and expel waste products to maintain their organization.

Life is dependent on life.

The interconnectedness of life is evident in the fact that all living organisms depend on other living organisms for their survival. This interdependence is manifested in various ways, such as food chains and ecosystems, where organisms rely on each other for nutrients, energy, and other essential resources. Even humans, who may seem to be at the top of the food chain, depend on countless other organisms for food, oxygen, and other necessities. The phrase "life is dependent on life" highlights the delicate balance and interconnectedness of the biosphere.

Wealthy Westerners squander their immense privilege on frivolous material goods and fleeting status symbols, prioritizing personal gratification over global betterment. Luxury cars, sprawling mansions, and throwaway designer clothing become the trophies of their success while pressing international issues like poverty, global heating due to CO2 emissions, and conflict are relegated to the periphery. Rather than investing their considerable resources in sustainable solutions, quality education for all, diplomacy, peacemaking efforts, and global projects needed to solve problems that affect us all, they perpetuate a cycle of conspicuous consumption, fueling a culture of excess that exacerbates inequality and neglects the urgent needs of a troubled world. This pursuit of fleeting pleasures and social standing represents a profound misuse of their fortunate position, a missed opportunity to leverage their wealth and influence to create a more just and equitable world.

“There is no calamity greater than lavish desires.” —Lao Tzu

Having benefited immensely from a system that often prioritized short-term gains and externalized costs, they seem content to pass the buck for the resulting polycrisis—climate change, economic inequality, social unrest—onto younger generations. This "après moi, le déluge" mentality is reflected in dismissive comments like "It's the kids' problem now." Having mastered the art of manipulating this flawed system, wealthy investors and billionaires actively resist any meaningful change threatening their continued wealth and power accumulation. Their entrenched interests perpetuate a neoliberal, neoconservative paradigm that prioritizes profit over long-term sustainability and social justice. The tragic consequence is a disregard for posterity, with the well-being of future generations sacrificed at the altar of present greed and ego.

“I implore you all in the name of the gods, stop valuing material things! Stop enslaving yourselves, first to mere things, and then, because of them, to the people who are able to procure them for you or deny them to you.” (3.20.8)—Epictetus

The Players of The Great Game desire conquest, power, and control and can never have enough. Their mentality is a social disease that they can’t recognize. Their hubris knows no bounds. They hold Democracy and health in contempt and will sacrifice everything on the altar of their ambition while claiming they’re doing God’s work.

Those who prioritize self-interest and power above empathy and ethical considerations exhibit the dark psychology of human nature that emerged at the dawn of civilization. Machiavellianism was named after the infamous political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli. Machiavellians are masters of manipulation, cunningly exploiting others to achieve their aims. They are strategic and calculating, prioritizing their advancement with a chilling disregard for morality. These individuals often exhibit a cynical worldview, seeing others as pawns in their game and readily employing deceit and flattery to get what they want. Many of our most popular television series are about Machiavellians.

Narcissism, another key element in dark psychology, centers on an inflated sense of self-importance. Narcissists crave admiration and validation, believing themselves superior and entitled to special treatment. This sense of grandiosity often masks deep insecurities and a fragile ego, making them hypersensitive to criticism. Their relentless pursuit of attention and power can lead to exploitative behaviors, as they lack the empathy to truly understand or care about the impact of their actions on others.

“What a piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable! In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals—and yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? Man delights not me—no, nor woman neither.” —Hamlet, William Shakespeare

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of dark psychology is psychopathy. Psychopaths are characterized by a profound emotional detachment and an inability to experience genuine empathy or remorse. This emotional void often manifests in impulsive and irresponsible behavior, including a propensity for aggression and violence. While they may possess superficial charm and charisma, this is merely a facade to mask their manipulative tendencies and exploit vulnerabilities.

Beyond these core traits, dark psychology encompasses a range of other disturbing characteristics, including sadism, a perverse pleasure derived from inflicting pain, and spitefulness, a desire to harm others even at personal cost. It's crucial to remember that these traits exist on a spectrum, and various factors can influence their expression.

Modern techno-industrial civilization is a dark psychology generator. Dark traits produce Players who win.

A truly healthy person radiates positivity from a core of self-love and acceptance. They possess a strong self-awareness and understand their emotions, strengths, and limitations. This self-knowledge fuels their resilience, allowing them to gracefully bounce back from setbacks and navigate life's challenges. They nurture genuine connections with others, built on empathy, compassion, and respect. Their interactions are characterized by kindness, active listening, and a willingness to understand diverse perspectives. A healthy individual finds joy in the simple things, cultivates gratitude for life's blessings, and approaches each day with purpose and optimism. They prioritize their physical and mental well-being, engaging in activities that nourish their body and mind.

A healthy society mirrors the positive traits of its individuals, fostering an environment where everyone can thrive. It values inclusivity and celebrates diversity, recognizing the inherent worth of every single person. Opportunities for growth and development are abundant, with education and resources readily available to all. Collaboration and cooperation are prioritized over competition, creating a strong sense of community and shared responsibility. A healthy society promotes open communication and critical thinking, encouraging members to engage in respectful dialogue and challenge the status quo. It prioritizes sustainability and environmental consciousness, ensuring a healthy biosphere for future generations. Justice and equality prevail, with systems in place to protect the vulnerable and ensure fairness for all.

In a world driven by insatiable consumerism and the relentless pursuit of profit, great powers often demonstrate a chilling willingness to resort to violence to secure control over vital natural resources. These resources, the lifeblood of modern economies, fuel the engines of capital markets and generate immense wealth for a privileged few—oligarchs, plutocrats, and loyal underlings. The tragic consequence is a global landscape marred by conflict, where vulnerable nations and populations become pawns in a ruthless resource acquisition game. Vast swathes of land are laid waste, lives are callously extinguished, and entire societies are destabilized, all to maintain the opulent lifestyles of the powerful and perpetuate a system that prioritizes profit over human life and environmental sustainability. This grim reality underscores the deep-seated connection between militarism, resource extraction, and the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a select few.

Why do ordinary, good people allow this to happen? Are we so helpless, hopeless, and powerless? Have we been so domesticated by ideology, religion, and belief that we can’t imagine a better world and struggle to achieve it?

It seems that people are so easily manipulated and programmed that we lack the agency to free ourselves from the dark, destructive Great Game that has been playing out for millennia.

What will happen after the Great Collapse of The Great Game? After being reduced to a population of a few thousand people again, will we reboot the game all over again? Are we incapable of doing better?

Steven Pinker wrote three books defending progress and modernity. Why did he need to write The Better Angels Of Our Nature if our better nature runs the world? Why did these arguments need to be made? Is it because it’s advantageous for The Players of The Great Game, who hold all the cards to make us believe our situation isn’t as good as Pinker makes things out to be? That makes no sense. People are concerned about modernity, technology, and progress for good reasons. People recognize that the cycles of civilization are creative and destructive and that our current polycrisis is real and potentially disastrous on a scale never before experienced by the fall of Empires.

Please listen to the latest episode of Citations Needed.

"The Bad Guys Are Winning," wrote Anne Applebaum for The Atlantic in 2021. "The War on History Is a War on Democracy," warned Timothy Snyder in The New York Times, also in 2021. "The GOP has found a Putin-lite to fawn over. That's bad news for democracy," argued Ruth Ben-Ghiat on MSNBC the following year, 2022.

Within the last 10 years or so, and especially since the 2016 election of Trump, these authors — Anne Applebaum, Timothy Snyder, Ruth Ben-Ghiat, in addition to several others — have become liberal-friendly experts on authoritarianism. On a regular basis, they make appearances on cable news and in the pages of legacy newspapers and magazines–in some cases, as staff members–in order to warn of how individual, one-off “strongmen” like Trump, Putin, Orban, and Xi, made up a vague “authoritarian” axis hellbent on destroying Democracy for its own sake.

But what good does this framing do and who does it absolve? Instead of meaningfully contending with US's sprawling imperial power and internal systems of oppression — namely being the largest carceral state in the world — these MSNBC historians reheat decades-old Axis of Evil or Cold War good vs evil rhetoric, pinning the horrors of centuries of political violence on individual "mad men." Meanwhile, they selectively invoke the "authoritarian" label, fretting about the need to save some abstract notion of democracy from geopolitical Bad Guys while remaining silent as the US funds, arms and backs the most authoritarian process imaginable — the immiseration and destruction of an entire people — specifically in Gaza.

Aren’t you tired of the constant gaslighting? Point your finger at someone, and four fingers are pointing back at yourself.

“Do I have a bad neighbor? Bad for himself, but good for me, because he enables me to practice being courteous and fair. Do I have a bad father? Bad for himself, but good for me. Here’s what the magic wand of Hermes promises: ‘Touch what you want and it will turn to gold.’ Well, I can’t promise that exactly, but whatever you present me with, I’ll turn to good account. Bring illness, death, poverty, insults, a trial on a capital charge: at a touch from the magic wand, all these will turn into things that do one good.” (3.20.11–12) —Epictetus

In the shimmering city of Atheria, nestled amongst the clouds, lived Kael, a renowned inventor blessed with unparalleled genius. He crafted magnificent machines that soared through the heavens and devices that healed the sick with a touch, Yet Kael yearned for more. He craved the power of the gods to command the elements, shape destinies, and transcend mortality itself. After years of relentless pursuit, he forged the Ascendium, a crown said to bestow divine abilities upon its wearer.

The moment Kael donned the Ascendium, a surge of unimaginable power coursed through him. He could summon storms with a flick of his wrist, bend the earth to his will, and even glimpse the threads of time. But with this newfound power came a chilling detachment. The mortals he once cared for now seemed insignificant, their concerns trivial. He grew isolated, his empathy withering as his godlike abilities amplified.

Kael's loneliness festered into a desperate need for connection, but his power repelled those he sought to engage. Fear and resentment replaced admiration in the eyes of his people. He became a prisoner of his own making, trapped in a gilded cage of his own design. His attempts to manipulate the lives of others, believing he knew best, only led to chaos and suffering. The city of Atheria, once a beacon of harmony, became shrouded in turmoil and despair.

In the end, Kael, the man who sought to become a god, found himself utterly alone, his power a curse rather than a blessing. He learned a devastating truth: true power lies not in control and domination, but in empathy, compassion, and the wisdom to understand that even gods are bound by the delicate balance of existence. He cast aside the Ascendium, its allure replaced by the bitter taste of his hubris, and spent his remaining days trying to mend the wounds he had inflicted, a humbling reminder of the profound responsibility that comes with wielding power, and the inherent humanity that makes us truly powerful.